Why is it so difficult to find out about Children’s working conditions?

By Simone Scully

What were children’s’

working conditions really like? The answer

is not easy to determine. It would seem

that if you found an eyewitness account, a painting, or an interview with a

child worker, that the information would be reliable but that is not always the

case. There are several sources that

have been found by historians about child labour, which have turned out to be

very unreliable.

To figure out how reliable a source is, there are questions

that we must ask ourselves and information we must find out:

Firstly, we must

look at the provenance (background) of the source, asking ourselves the famous

“W” questions: Who? Why? When?

Answering these questions about the provenance will give us some

idea of how reliable the source is.

(Who?) If we know that the source was produced by someone who was in

favour of child labour, we know that the source will most likely be biased, in

favour of child labour, and will make child labour not seem as bad as it truly

was. (Why?) If we know that the person

that produced the source was making it for a newspaper that was going to be

read by mine owners, or people that would benefit from child labour, that the

source would most likely also be supporting child labour. (When?)

If the source wasn’t produced during the time it refers to, then the

information is liable to be distorted by time.

Secondly, we must ask ourselves are about the content of

the source. We must look to see if the

source is mainly facts, or opinions. We

must look at the language of the source: is it emotive? We must consider the fact that the source

may have been edited, for example, the recorded answers to an interview may be

different from the answers that the children actually gave…

Finally, we must look to see if there are other sources,

which contradict or corroborate (agree with) the source?

All of these questions must be considered. Historical sources are biased, and

unreliable, however, by asking questions, considering the context, we can get

some amount of reliability.

Here is an example. The source below is an interview of a child

factory worker. This is one of the

hundreds of interviews that the government produced in the year of 1831; it was

trying to find out information about the children’s working conditions in

factories. The government had chosen

several commissioners to go to various factories and mills to interview the

children. They asked the children about their hours of work, wages, accidents,

health, beatings etc. The commissioners

were to bring back written reports of the interviews such as the one below:

________________________________________________________________________________________

At what age

did you begin work in the mills?

I

was nearly eight years old.

What were your

hours of working?

From half past

five in the morning till eight at night.

How often were

you allowed to make water (go to the toilet)?

Three

times a day.

Could you hold

your water (urine) all that time?

No. We were forced to let it go.

Did you spoil

and wet your clothes constantly?

Every

noon and every night.

Did you ever

hear of this hurting anybody?

Yes,

there was a boy that died.

Did he go home

ill with attempting to suppress his urine?

Yes,

and after he had been home a bit, he died.

Were you

beaten at your work?

If we looked off our work or spoke to another we were beaten

What time of

day was it you were most beaten?

In the morning

And when you were

sleepy?

Yes

Was the mill very

dusty?

Yes

What effect did it produce?

When

we went home at night and went to bed, we spit up blood.

Had you a cough

with inhaling dust?

Yes, I had a cough and spit blood

___________________________________________________________________________________________

The source above was believed for many years to be very

reliable as it was an official government report. However, the source is actually very unreliable in many ways.

Though the source is an interview, and we are certain that

the questions were asked to children that worked in the factories, there are

several things that tell us that the source is unreliable in the following

ways:

1.

It is clear that the questions in the interview

are leading questions, meaning that the interviewer was asking the question in

a certain way so that the children would give them the answer they wanted.

2.

It is suspected that factory reformers could

have told some of the children what to say, so as to make the conditions seem

worse.

3.

The commissioners were actually against child labour,

which means that they might have picked children that were more likely to give

the answers that they wanted to hear in their interviews.

4.

The children could not read or write, therefore

they were not the ones that wrote down the answers in the report. The commissioners could have edited the

answers, so that they sounded even more terrible.

5.

Children, when asked questions by adults, tend

to give the answers adults want to hear.

The children interviewed could have been afraid or intimidated by the

commissioner and did not want to get the commissioner angry with them, so

therefore the children gave him the answers they believed the commissioner

wished to hear.

However, the interview can provide reliable

information. Obviously, as it was

factory child workers that were being interviewed, as the information is

first-hand and eyewitness, the details from the source have to have

happened. Perhaps, it was not in the

same way as implied in the interview.

The interviews do give us details about what it was like in the

factories for child workers.

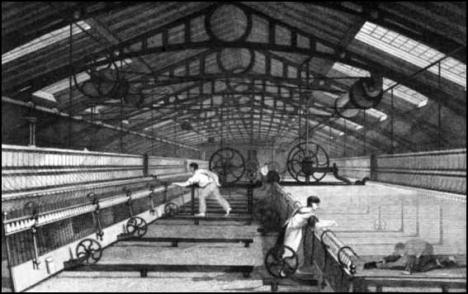

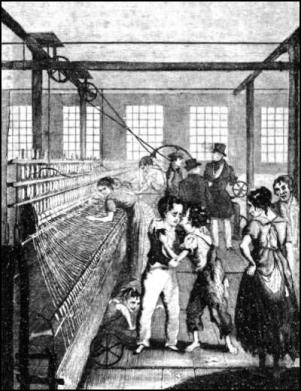

We do not know who the artist of the above picture is; so

we cannot be sure of the background behind the picture, and the context in

which it was made. However, we do know

that the picture was printed in a book called: The History of Cotton

Manufacture in Great Britain, which was published in 1835 and written by Edward

Baines.

Edward Baines was an

editor of a newspaper, which was mostly read by mill owners, and supporters of

child labour. We know that Edward

Baines often supported the mill owners’ point of view.

Although we don’t know who the artist was, we can guess

that he favoured child labour from content of the picture. The factory is too peaceful; it is women

that are doing the work (which gives the feeling that the work is easier);

there are very few children (the children that are working in the picture are

doing safe and easy work) and their clothes are of good quality and clean. We know that work in the mills was not this

way. Too many sources contradict that idea.

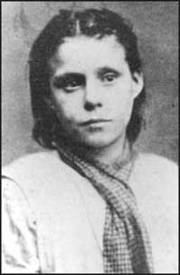

This picture is completely opposite of the previous one. Children are crawling under the machines;

the clothes worn by the workers are torn and dirty; there are overseers in the background;

the machines look more dangerous and the factory is not as clean looking as the

previous one.

Again, we do not know who the artist of this source is, though we

do know that the picture appeared in a novel in 1840, written by Frances

Trollope. This book, The Life and

Adventures of Michael Armstrong, was a fictitious story about an orphan boy,

who worked in a factory, and was very mistreated.

Since the book is

fictitious, not all the events necessarily happen and some may have been

exaggerated. However, some of the

events in the book had to be true or it would not have accepted. Also, we know that some of the facts in the

book had to be true because the author based her book on a real factory

apprentice called Robert Blincoe.

Two other sources that

contradict each other are the following:

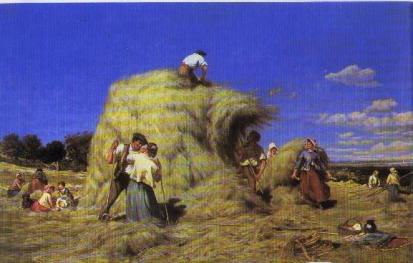

The picture above

shows child labour in fields and that it was exhausting. It suggests that

children got very little rest (shown from the boy that collapsed). Also, there is an overseer in the background

watching and making sure that they continue working. This source is completely different from the next one:

In this

picture, the work looks voluntary: there is no overseer, and the children in

the picture seem to be resting. There is

plenty of food, so it gives the impression that if they wish to rest and eat,

they may. In the front of the picture,

two people appear to be talking amiably.

It is very clear that the two sources contradict each

other. Even in terms of style. One is in black and white, making the work

seem hard and dreary, while the other one is in colour, with a blue sky above,

making it look peaceful.

The source that follows is an extract from a burial register in

Somerset:

_______________________________________________________________________________

30 August 1820

Frederick William Bond age

twelve

Head fractured by kick from

a horse in Clandown coal pit

14 December 1821

William Bourne age nine

Killed by falling down

Ludlow coal pit 24 fathoms (122 feet)

26 November 1824

George Chappel age eight

Killed by falling down

Ludlow coal pit

4 October 1835

John Ashman age eleven

Killed by falling down

Tyning coal pit

16 November 1842

Joseph Parfitt age nine

Killed by bad air in coal

pit.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Burial registers are very useful. They tell us about the different ways in which

child workers died.

But this source can also unreliable. It is hard to believe that only five

children died in 22 years. This makes us believe that the burial register did

not record all child workers’ deaths.

It is very possible that some of the deaths were not recorded because

the mine owners were ashamed and didn’t want to admit that that many children

could die in the mines or perhaps the deaths were also not recorded because the

children were poor, or orphans.

The next source is different, though it does

corroborate in many ways the burial register.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Janet Cumming,

A coal bearer, eleven years

old

I

go down with the women at five in the morning and come up at five at

night. I carry the large bits of coal

from the wall face to the pit bottom.

It is some weight to carry. The

roof is very low. I have to bend my

back and legs and the water comes frequently up to the calves of my legs. Have no liking for the work. Father makes me like it. Never got hurt, but obliged to scramble out

of the pit when the bad air was in.

Alexander Gray,

A pump boy, ten years old

I pump out the water in the

under bottom of the pit to keep the men’s rooms (coal face) dry. I am obliged to pump fast or the water would

cover me. I had to run away a few weeks

ago as the water came up so fast that I could not pump at all. The water frequently covers my legs. I have been two years at the pump. I am paid 10d. a day. No holiday but the Sabbath. I go down at three, sometimes five in the

morning, and come up at six or seven at night.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The previous source is an extract of a royal commission, which was

set up in 1840 by the government to find out about the working conditions in

the mines. It took two years for these

reports to be finished. Today, these

documents provide us with some very interesting information. Back in 1842, people who were against the

reforms claimed that these reports exaggerated the bad conditions. They claimed that the children lied about

their work, that the commissioners asked leading questions and that the people

interviewed were the very worst cases of child labour in the mines.

All these

claims about the commission could possibly be true. The questions were not

written down, so therefore, we do not know if they were leading questions. Also, the ages written down in the source

could be false, because at that time, there were no birth certificates to prove

people’s ages. The children could, for

example, have claimed that they were ten, but there is no proof that they

actually were.

As in all

written sources, or interviews, there is the possibility that the commissioners

could have edited the answers to make the report of what is was like sound

worse, so that the government would do something about it.

As I said,

this source in many ways corroborates the burial register. Both talk about bad air, and that the work

in mines was dangerous. This source

also corroborates other sources as well, such as the other interview source

(about the mills). Even though that

source is not about the mines, both say that child labour was horrible and both

say that the children worked long fatiguing hours.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The

commissioners expected and desired to find ill treatment of children. Their instructions were to examine the children

themselves, artful boys and ignorant young girls, and to put questions in a

manner, which suggested the answer.

The

trapper is generally cheerful and contented, and to be found occupied with some

childish amusement, such as cutting sticks, making models, and drawing figures

with chalk on his door.

_______________________________________________________________________________

The source

above is very critical of the commissioners and their interviews of young

children. It is an extract of the Marquess of Londonderry speech, when in 1842 he

attacked the report from the House of Lords.

The Marquess of Londonderry owned many pits in the northeast of England,

and was strongly against the reform of child labour. If the government decided

to stop children working in mines, his profits would fall, along with the

profits of many other mine owners.

This source is

in disagreement with many other sources.

It is very unreliable, especially in regards to the trapper. It was dark in the pits, and the children

could see very little. It is clear to us

that there is no way that the children could have cut sticks, made models or

drawn on the doors.

From all of

these sources, historians can make some assumptions about what child labour was

actually like. It takes many sources

for historians to make conclusions on what has happened in the past, such as

child labour. Today, we still aren’t

sure about what child labour was exactly like, though we can certainly make

good guesses, and we are very certain that it was dangerous and cruel. Many, many children died, became ill or were

injured very severely, loosing legs and arms.

The answer to

the question: what were children’s working conditions really like, is not easy

to answer. Why is it so difficult? It is difficult to find out the answer

because historians must be careful.

They must beware of propaganda and opinions.

In the future,

some hundred years from now, historians will be asking similar questions about

our working conditions. How reliable

will their sources be?