|

There were also strong economic ties between the Church and the people.

All land that did not already belong to the Church was taxed for the benefit

of the Church. One tenth (a tithe) of everything produced on this land was

given to the Church. In addition, the Church itself did not pay taxes on

anything donated to it. Pilgrims who expected a saint to produce a miracle,

were expected to make an offering to the saint's church. As a consequence, the Church became very rich. By the end of the middle ages, the Church owned

approximately one third of all the farmed land in Catholic Europe!

The Church also strictly

controlled people's everyday life. Everyone belonged to their local

parish. From managing the important civic ceremonies of birth, marriage and

death, to organizing the festivals associated with Holy days, the Church was

responsible for all aspects of village social life. Most importantly, the

parishioner attended a weekly Sunday ceremony (Mass) and regularly told the

priest all their most personal secrets (Confession).

Politically, economically

and socially, the Church exercised an all-embracing 'Catholic' influence but

it was the cultural influence that was most important of all. By controlling

the minds of medieval men and women, by influencing how people

explained what happened to them, the Church had no need to physically force

people to do things.

Medieval people were

fatalists. They believed that everything that happened because God wanted it

to happen. Nothing happened naturally, everything happened because of

'divine intervention' (God's actions). When good things happened people were

being rewarded by God and they thanked him. When bad things happened, they

were being punished for something doing something sinful. Medieval people were constantly on

the lookout for signs or omens of God's moods. For the people of Paris, a

red sky at night three times in a row, was an sign of war; the appearance of

Halley's comet in 1066 was shown on the Bayeux Tapestry, as an omen of

the great upheavals to come.

|

|

Life for medieval people

was a constant struggle between the forces of good and evil. They believed

that good and evil actually existed in objects all around them (pantheism)

The reason for this predates the Christian faith. In particular, the Devil

was to be found all around, tempting people away from good Christian

behaviour. Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny in the the 12th century

collected stories about the Devil and listed over 1000 different forms that the Devil may

take, including spider, vulture, bear and black pig. For St. Bruno the Devil

actually existed, invisible in the air around us: 'a breath of wind, a

turbulence in the air, the gust that blows men to the ground and harms their

crops, these are the whistlings of the Devil'.

|

But it was with illness or

in the face of death that medieval minds became most obsessed with good and

evil. Only

the priest could save the individual soul from eternal damnation and

purgatory. Hell was a possibility that filled people’s minds with horror and dread.

Richard Alkerton a preacher in 1406, described the eternal nature of Hell

that would have been familiar to medieval people:

'boiled

in fire and brimstone without end. Venomous worms...shall gnaw all the

members unceasingly, and the worms of conscience shall gnaw the soul... Now

ye shall have everlasting bitterness... This fire that tormenteth you shall

never be quenched, and they that tormenteth you shall never be weary neither

die.'

|

|

|

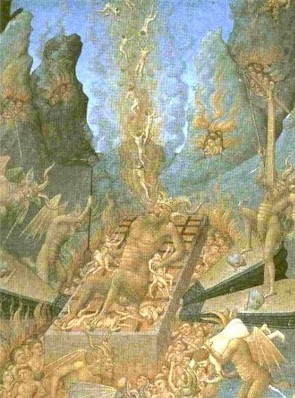

(above) A medieval

vision of Hell |

In the absence of

scientific explanation Illness in general was seen as an invasion of the

body by the Devil. Gregory of Tours claimed that the Devil could be vomited

up. Common 'cures' such as bleeding and drilling holes in the head were similar attempts to persuade the Devil to leave the body. To be in the

presence of something holy, the relic of a saint for example, would

hopefully bring about a miraculous cure. This was probably the main reason (motive)

for people undertaking a pilgrimage. As Chaucer explains in the Canterbury

Tales:

'The

Holy blisful for to seke

That them hath holpen whan that they were sick.'

|